Asha and David: What Kenya’s New SHA Policy Means for Salaried vs. Self-Employed Citizens

It arrived for Asha in the cold, impersonal glow of a computer screen. An email from HR with the subject line: “Important Update: Transition to Social Health Authority (SHA).”

For David, it came as a worried whisper across a dusty workshop, carried on the scent of sawdust and varnish. “Umesikia hii maneno ya 2.75%?” Have you heard this talk of 2.75%?

One policy. One nation. Two vastly different realities.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: The World Before—Life Under NHIF

- Chapter 2: The Catalyst—The 2.75% Mandate Arrives

- Chapter 3: The Maze of Implementation—Registration and Compliance

- Chapter 4: The Moment of Truth—Using the SHA Cover

- Conclusion: The New Equilibrium—Mastering Your Reality

Chapter 1: The World Before—Life Under NHIF

Before the emails and the whispers, there was a familiar rhythm.

Asha’s Reality: The Predictable Deduction

Asha’s financial life is one of structured predictability. On the 25th of every month, her gross salary of KES 80,000 lands in her bank account. From it, various lines are neatly subtracted: PAYE, NSSF, and the familiar NHIF contribution.

Under the old system, her NHIF deduction was a fixed KES 1,400 per month. It was a number she had long since factored into her budget. It was the cost of knowing that if her five-year-old son, Leo, got sick, a visit to their preferred mission hospital was covered. For Asha, NHIF was a simple, automated part of her salaried life—a background process she rarely thought about.

David’s Reality: The Jua Kali Hustle

David’s financial life is a dance with uncertainty. As a skilled carpenter making bespoke furniture, his income is a tide that ebbs and flows. A good month might bring in KES 55,000. A slow one, maybe KES 25,000. On average, he clears about KES 40,000.

His NHIF contribution was a flat KES 500 per month. It was a bill he had to remember to pay. Sometimes, when a client delayed payment or a big project fell through, that 500 shillings was a struggle. He’d have to choose between paying for the cover or buying a crucial tool. He was diligent, but the mental load was constant. For David, NHIF was an active, manual expense—a line item in his "must-pay" list, right next to workshop rent and supplies.

For both, the system was imperfect but known. An established quantity. That was about to change forever.

Chapter 2: The Catalyst—The 2.75% Mandate Arrives

The new Social Health Act didn't just propose a change; it mandated one. The flat rates were gone. In their place, a single, sweeping figure: 2.75% of gross salary or gross earnings, with a minimum of KES 300 and a maximum of KES 5,000.

Asha’s Experience: The Corporate Memo

Asha read the HR email three times. It was professional, full of links to government websites, and reassuring phrases like "seamless transition." But her eyes were fixed on the calculation.

- Gross Salary: KES 80,000

- New SHA Contribution (2.75%): KES 2,200

Her monthly healthcare deduction had just jumped from KES 1,400 to KES 2,200. An increase of KES 800.

Her mind immediately began to race. “Okay, 800 shillings. That’s my weekly transport to work. That’s a top-up on our electricity tokens. That’s a portion of what I try to put into Leo’s education savings account.”

The change was being handled for her, but it was being done to her budget. The automation of the salaried world felt less like a convenience and more like a loss of control. The question wasn't how to pay it, but how to absorb it.

David’s Experience: The Workshop Rumour Mill

David heard the news and felt a knot tighten in his stomach. He and his fellow artisans gathered around a smartphone, scrolling through a news site. The language was confusing—"households," "gross earnings," "means-testing." All he needed to know was the bottom line. He did the math on his average income.

- Average Monthly Earnings: KES 40,000

- New SHA Contribution (2.75%): KES 1,100

His mandatory contribution had more than doubled, from KES 500 to KES 1,100. An increase of KES 600.

For David, this wasn't about reallocating funds from a savings column. This was KES 600 that had to be carved out of essentials. “That’s two bags of maize flour,” he thought. “That’s the cost of a new saw blade. That’s money I need to find, every single month, whether I have a good month or not.”

His burden wasn't just financial; it was administrative. No HR department was going to do this for him. This was a new, heavier weight he had to carry himself.

Chapter 3: The Maze of Implementation—Registration and Compliance

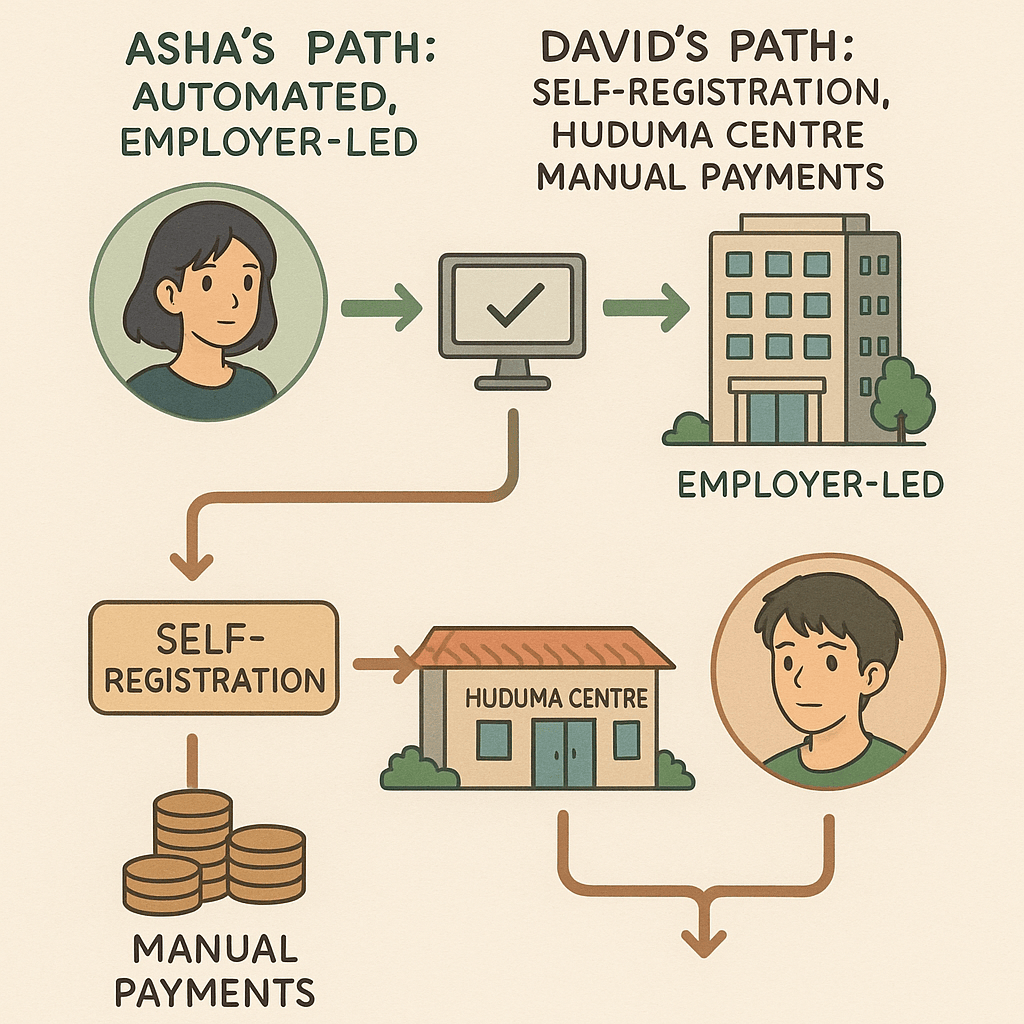

With the financial shock absorbed, the next hurdle was the practical one: getting into the new system. Here, the paths of our two Kenyans diverged completely.

Asha’s Path: The Automated Hand-off

For Asha, the process was invisible. Her employer’s payroll software was updated. Her details, already in the KRA and NSSF systems, were likely ported over. Her role in the transition was entirely passive.

Her "maze" was one of information. She found herself asking:

- “Are my details correct? Is my son still listed as my dependent?”

- “What does this new cover actually entitle me to? Is it better than the old NHIF Supa Cover?”

- “Do I need to do anything, or just trust the system?”

Her challenge was not action but assurance. She needed clarity that the new, higher deduction was buying her better, more reliable security. Her struggle was fought through company intranets and by reading articles like this one, trying to piece together a picture of her new benefits.

David’s Path: The Digital Frontier

For David, the process was a hands-on, multi-step ordeal. He was now responsible for formally declaring his income and registering himself as the head of his household. His journey looked something like this:

- The Portal: He first tried the self-registration portal on his phone. The site was slow, and a few required fields were unclear. What did "proof of income" mean for a freelancer with no payslips?

- The Huduma Centre: Frustrated, he decided to visit a Huduma Centre. He took a morning off work—losing potential income—and waited in line.

- The Declaration: At the counter, he was asked to declare his average monthly income. This brought a new anxiety. If he declared his average of KES 40,000, his payment would be KES 1,100. What if he had a terrible month and only made KES 20,000? The system demanded a predictable number from an unpredictable life. He honestly declared his average, knowing he'd have to build a buffer for lean times.

- The Payment: He was shown how to pay via the government paybill number using a unique reference code for his household. This was now a monthly, manual task he could not afford to forget.

David’s challenge was action and consistency. He had to fight through bureaucracy, overcome technical hurdles, and impose a rigid financial discipline on a fluid income. The system was not built with his reality in mind; he had to bend his reality to fit the system.

Chapter 4: The Moment of Truth—Using the SHA Cover

A policy is just a theory until the day you need it. Let’s imagine that day arrives for both Asha and David.

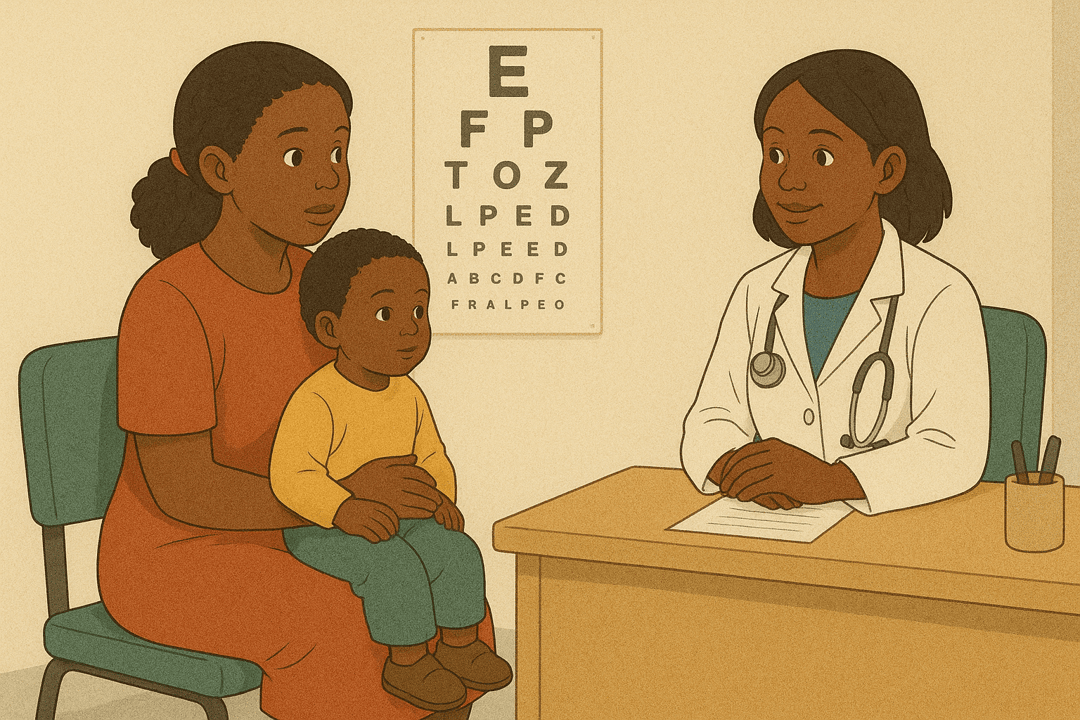

Scenario 1: Asha’s Son Needs Care

Leo, Asha’s son, wakes up with a high fever and a persistent cough. Asha knows she needs to see a doctor.

- The Process: Under SHA, her first stop is a designated Level 4 primary healthcare facility. Her employer's insurance broker had already sent a list of accredited hospitals in her area. She takes Leo to one.

- At the Hospital: At the reception, she presents her new SHA card (or uses her ID number). The clerk verifies her status in the system. Because her employer has been making the deductions, she is marked as "Active."

- The Experience: Leo is seen by a doctor, gets a prescription for antibiotics and fever reducers, and they head to the hospital’s pharmacy. The consultation and the generic medications are fully covered by the Social Health Fund (SHF). She pays nothing out of pocket.

- The Takeaway: For Asha, the system works smoothly. The higher premium translates into a seamless point-of-service experience for primary care. Her passivity in the registration process pays off here, as the automated system ensures she is always compliant.

Scenario 2: David Injures His Hand

While finishing a cabinet, David’s chisel slips, causing a deep gash in his hand that needs stitches.

- The Process: His workshop is close to a local public health clinic, a Level 3 facility. He rushes over, his hand wrapped in a cloth.

- At the Clinic: He presents his ID. The clerk checks his SHA status. This is David’s moment of truth. Had he remembered to make the KES 1,100 payment for this month? Thankfully, he had paid it three days prior. The system shows him as "Active."

- The Experience: A clinical officer cleans the wound and gives him five stitches. The procedure and a tetanus shot are covered. He is given a prescription for painkillers to buy at a private pharmacy, as the clinic’s stock is low—a real-world hiccup. The emergency treatment itself, however, costs him nothing.

- The Takeaway: For David, the system also works, but his access was entirely dependent on his own recent action. If he had been a week late with his payment, he could have been declared "in default" and forced to pay for the treatment himself before being reinstated. His well-being is directly tied to his personal financial diligence.

Conclusion: The New Equilibrium—Mastering Your Reality

The stories of Asha and David are not just tales; they are roadmaps. They reveal the fundamental truth of the Social Health Authority: it is a universal policy with deeply individual consequences.

By walking their parallel paths, we arrive at a clear destination.

For the Salaried Kenyan (The Ashas): Your Power is in Knowledge. Your path is one of automation, but this convenience can create a dangerous blind spot. Your battle is against passivity.

- Scrutinize Your Payslip: Don't just see the deduction; understand it. Ensure the 2.75% calculation is correct.

- Demand Clarity: Your employer and HR department are your primary resource. Ask them for details on the benefits package. What tier of hospitals can you access? What does it cover?

- Know Your Dependents: Verify that your spouse and children are correctly registered under your household. Don't assume the data was ported correctly.

- Think Hybrid: Understand that SHA is a foundation, not the entire building. If your employer offers a private top-up, understand how it complements your SHA cover for access to premium hospitals or specialized care.

For the Self-Employed Kenyan (The Davids): Your Power is in Discipline. Your path is manual and requires constant vigilance. The system is not designed for the beautiful chaos of your entrepreneurial life. Your battle is for consistency.

- Treat SHA as a Prime Cost: Your 2.75% contribution is no longer an optional extra. It is a non-negotiable cost of doing business, as essential as your rent or materials. Budget for it first, not last.

- Create a Buffer: Given your fluctuating income, calculate your 2.75% based on your average or even a good month. In lean months, you’ll have a cushion to draw from to make the payment. Falling behind is not an option.

- Go Digital and Keep Records: Embrace the digital payment methods. Set a recurring monthly reminder on your phone. Save every payment confirmation message as proof of compliance.

- Honesty in Declaration: While tempting to under-declare income to pay less, this can create problems down the line, especially if the system incorporates KRA data more tightly in the future. Declare honestly and plan accordingly.

The Social Health Authority is here. It is a new pillar in the architecture of our lives. Whether you are an Asha, experiencing it as an automatic shift in your finances, or a David, feeling it as a new monthly responsibility you must shoulder yourself, the goal is the same: to move from confusion to clarity, from anxiety to agency.

💡 > By understanding your unique journey, you can master this change, ensuring that when you or your family need it most, the promise of health security is not just a policy, but a reality.

Ready to Get Started?

Get personalized advice and quotes tailored to your needs. No pressure, just honest guidance.

👉 Or start a chat with our assistant now.